I drafted this article after I’d been in a metaphorical decompression chamber for about a week, since leaving that last ship. A little 25 Gross Ton workboat. I’d been on her for only a few days before that visit, so I didn’t know the guts of her well. This time I spent 21 days on board, although I was living ashore at night.

That trip took a toll on me.

The beginning of the trip was chaotic and hurried. The middle was marked by technical faults and a rush to get the ship seaworthy to go on charter in Sassnitz. The steam back up to Sassnitz from the shipyard felt like a blessed relief, as we now had full steering and use of thrusters. Shiphandling became a dream, and I could finally enjoy the beautiful waterways of Germany in autumn. Our speed rocketed from 12 to 20 knots. However, this romp around the primordial Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Baltic coastline became increasingly tense as the last dregs of summer boaters and commercial fishermen converged on the foggy coastal corner at the white cliffs of Rügen.

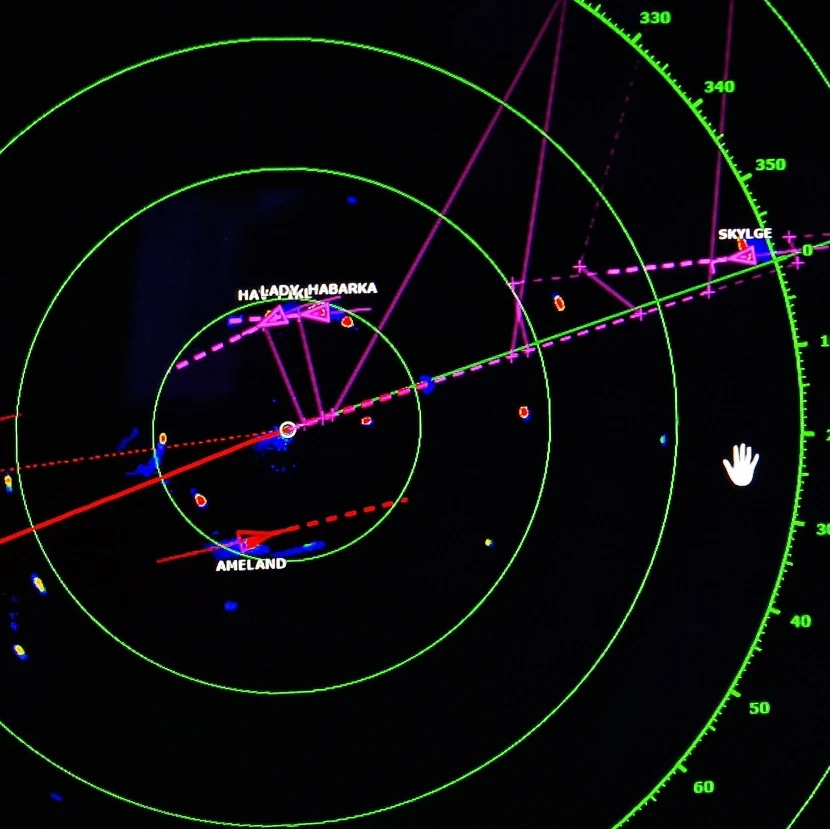

Thick fog has long been the mariner’s foe. Even with modern marine radar, you can’t pick out all of the small dinghies, fibreglass recreational craft, sailing yachts and timber fishing boats that you normally steer clear of by use of the mark-one-eyeball. Even detection of a contact by radar comes with the attendant doubts due to delays in computer processing, and lack of a visual cross-check.

Reduced speed and hyper-vigilant visual lookout are required. Last-minute alterations of course are occasionally necessary as contacts emerge from the gloomy soup. Collisions at sea are bad for your career. To avoid this, the focus of a hunter is required, sometimes for hours on end. I cursed mightily at four middle-aged German men wearing dark grey jackets, sitting 18 nautical miles offshore in an unlit rubber dinghy, drinking beer, fishing, and managing not to be capsized only by dumb luck.

I got my fill of the sea on this trip.

It wasn’t the two separate incidents of taking on water. It wasn’t the dozen or so safety deficiencies that we tolerated in order to meet commercial pressure. It wasn’t being left alone without an engineer on board, and being expected to fix broken generators, steering and engines. It was the attitude of the vessel manager that really did me in this time.

I broke my back pushing the operation of the ship to the limits of every regulatory grey area I could muster, in order to ensure my client didn’t disappoint their client. I saved them thousands when I needn’t have and certainly helped them retain a charter worth £100K+ when I could easily have put my feet up and refused to sail. Only to be ‘nickel-n-dimed’ out of about £20 worth of travel expenses on my October invoice.

That really angered me. It wasn’t the mild moments of safety concern. I only had a couple of moments of fear and apprehension. It was the expectation that I should break and bend the rules for the client, but that he shouldn’t do me a single favour, and stick only to the letter of the law.

The lack of self-awareness and reciprocity among corporate middle managers crosses all industry boundaries.

Ho hum. Good ammo for the management book I’m writing.

The flooding was of minor concern. The bilge pumps that remained in operation appeared to be expelling water slightly less quickly than the rate it was coming in, and we didn’t have far to go for shelter.

Somehow, we ended up without certain electrical facilities, for a wee while. A Captain is not an electrician, so I telephoned the company’s duty engineer for advice.

‘I think I need to switch the inverter back on mate. But, the electrical compartment has about 5 mm of water sloshing around the deck. There are bare wires and circuits everywhere.’

The electrical compartment below the wheelhouse was designed by an extraordinary naval architect, who decided on an efficient design solution by housing a water tank and half a dozen freshwater pipes together with all of the main circuitry for the vessel’s navigation systems, inside a space roughly the size of two coffins. The space was pitch black, with the unsettling combination of the sounds of electrical humming and water sloshing. Made all the more atmospheric by a complete absence of light.

‘If you’re worried about being electrocuted, just poke it with an electrician’s screwdriver. Then you won’t get electrocuted’.

Aha.

‘Alrighty then. Nae bother. I’ll call you back and let you know if I’ve died’.

The days after that went by with something of a routine. A 5.30 am start, we would wander down to the boat, and like a Nucor Steel employee, give it hell for twelve hours before knocking off. Eat. Sleep. Laundry. Emails. Homework. Repeat.

After about 15 days, the vessel was officially ‘on-hire’ to the charterer. At this time, I was provided with two ‘generator technicians’ from the UK. Technically these ‘Industrial Personnel’ are passengers, and not expected to assist with the vessel. Fortunately, however, they were a right couple of geezers from England. After only mild persuasion, they proved their utterly marvellous abilities with mechanics and were able to get our water-logged and shorted electrics, fans, generator, etc back up and running before the client had a chance to give us an on-hire survey.

It took me three days to dry out the paper charts (maps of the sea), manuals and books with a little electric space heater. I spent evenings at the Air b-n-b updating and correcting them. I had to put right paperwork that had been left undone for almost two years. Particularly annoying, since I had my own overtime to do, without back-dating work that was generated by other people’s neglect and incompetence.

I blame the UK Coastguard as much as anyone else. At the lower tonnage of licenses, they really do not require any training in safety management at all. And when they set the ‘minimum safe manning’ requirement for a vessel, they invariably fail to consider the actual operational requirements for a vessel in an emergency situation. We are always chronically short-handed.

Safety first! Unless the government gives you an exemption, I guess. Then it’s a race to the bottom in terms of standards, and you have a piece of paper saying it’s OK to ignore the crew’s professional judgement.

Terribleness of the job aside, I did start to grow really quite fond of this corner of Germany once I got to know it a bit better. Three days in Rostock, the daily commute between the accommodation in Sagard and the ship in Sassnitz, and multiple car and rail journeys around the island trying to source parts and equipment locally did give me time to imbibe the essence of the culture. As did the five-hour train journey to Berlin when I signed off.

Unlike the Netherlands, Sassnitz and Rostock really felt like Northern Britain in many ways. These were working-class towns, with beautiful older properties in villages bounded by later social housing projects. The older people are fat and disgruntled, just like us. Smoking cigarettes, with their bellies protruding from their working coveralls. Stopping at the shops for a quarter bottle of hard liquor, chocolate, a newspaper and 2 kilos of tobacco on the way home after a long shift. Kebab shops nestled between the LIDL and ALDI. Teenagers smoke and drink beer outside the Edeka.

I loved it. I felt right at home among these people. Clearly, they were grafters, with a long intergenerational feeling of disappointment in their hearts. Just like the Scots, and the Northern English.

And I really appreciated the things that were better. The German reputation for workmanship is well deserved, and not just confined to the building of luxury cars that seemed to be commonplace. Their social housing apartments are immaculately clean, whereas their British counterparts might have unkept lawns, garbage in the common areas, or graffiti and the occasional plywood window, the Germans live in scrupulous good order. Maintenance is easier in a drier climate, true, but their discipline is evident on every moss-free surface and mural-decorated gable end.

The use of precisely manufactured aluminium, steel and concrete building materials where the Brits would use cheap and perishable decking boards or crumbling postcrete lends a quality of solidity to their built environment. Their historic buildings are preserved in character but are not restricted from having clean modern finishes to window frames or adding smart electrics to the exterior. And if you love gardening, as I do, you could spend a happy few hours googling or searching Pinterest for images of the German phenomena known as the ‘Kleingarten’.

A Kleingarten, meaning ‘little garden’, is akin to an allotment. But the difference between a British allotment and a German Kleingarten that is lost in translation is the sheer German character that is on display as our Saxon cousins apply excellence through engineering to their cabbages, sheds and fences, with as much love, care and dedication as any Audi engineer.

What lavish and wonderful places German gardens are. Productive, with fruit in summer, and winter vegetables raised neatly in well-kept beds. Clean, with designated areas for compost, and even some with their own recycling bins. Beautiful, with flowers, grasses and mature trees at the ends of beds, or sculpting spaces. Orderly, with fences, and seating and decking. Luxurious, with potting sheds that could pass for an Air BnB in London. (Literally, I saw several built of concrete, with patio doors and satellite dishes). And as with everything German, well maintained.

But their gardens are unlike their agricultural fields, which seemed not to be enclosed by fences, only ditches and brand new tarmac roads as smooth as the surface of glass. The German attitude to boundaries is strong, with the Kleingarten district of each town defined with the tight control of a central planner. The irrepressible and untameable urge to put your hands in the soil and create life and beauty is restricted and permissible only in designated areas. Imprisoned like great art kept in frames, behind ropes in buildings designed to look like a madhouse of pretentiousness. All our modern societies put art in cages like this, lest the spirit or emotion of such beauty leak out into the general populace, and outbursts of individuality or emotion ensue.

The amazing orderliness of German society speaks to you loud and clear. Particularly on bank holidays, when literally every single business closes. Not even a Chinese restaurant will remain open.

My semi-toothless cockney generator technician (unironically) commented that he remembered a time in England when: ‘shops would only open for a couple of hours on bank holidays. But that was back in the 70s. That was back when white people still owned sweet shops’.

Again, my friends, no HR officer on these little cargo ships.

The frustration of the youth is milder in Northeast Germany than it is in Britain, although the bitterness leaks out here and there. The aforementioned quiet restoration of the monument to Lenin’s October Revolution. The ‘All Cops Are Bad’ graffiti dotted around public transport stops and suspiciously near the University. (Although my sand-dancer mate assured me he’d seen ‘All Coppers Are B*stards tattooed on several of his jailbird friends knuckles long before BLM was a thing). The resurrection of Norse religion, seen in the runic tattoos and Viking-esque haircuts of young men. Communist rainbows haven’t quite made it onto flags yet, but a few little stickers caught my eye.

I understand the feeling that you can’t win, and that society is stacked against you. Inflation and the magic Money Tree have built a world that blew marx’s theory out of the window. There are only two classes. Those on the inside of inflation, and those on the outside.

Everything is expensive in Germany. I walked through car dealerships to look at vans (I’m van-curious). Second-hand VW transporters were retailing for fifty thousand euros! Food was expensive. I ended up way over my planned expenditures for the trip. And the Del-Boy of Sagard who ran our accommodation demanded five euros from me every time I used the washing machine. (That guy couldn’t speak a word of English but was wearing some sort of karate outfit all the time, that said ‘Yakuza, F*ck Society’! across his chest).

I refused to pay for the laundry and passed it on to my client. I’m fairly sure that guy was into some dodgy nocturnal activities and some might have thought him intimidating, but I’m large enough myself to not have to worry about shin-kickers like him.

The only things I noticed that were abundantly cheap in Germany were alcohol, chocolate, and cigarettes. Something I approve of generally, but not in the case of Germany. It’s clear that these commodities are not subject to such outrageous ‘sin-tax’ that we endure in the UK for the simple reason that sugar, stimulants and depressants are permissibly cheap so that the working man can lubricate his way into accepting the hard strictures of the social order.

Strictness and adherence to rules are something Germans have long been caricatured for. ‘Show me our papers’ always comes to mind with a fake comedy German accent. But with good reason.

The high street in Sagard hosts a grand and worryingly permanent-looking building that contains a Coronavirus Testing Centre. The bus drivers and train conductors enforce mask mandates on public transport. (Eventually, I found some larger and less agreeable male conductors perfectly willing to shout at me in German, despite earlier observations). And old people frequently wore masks in shops, and glared and tutted, shamingly, if you get too close.

There was no decorum when waiting in line at supermarkets. As another checkout opened, old people literally dived in and pushed past me to get there first. Something unthinkable in Scotland, where the standard etiquette is to politely ask the person behind you if they’d like to go first if they are in a hurry.

Germans are clearly wealthier on the whole, with a healthier middle class than their British equivalents. And their tortured youth have the air of Long-Island Limousine Liberals. The Ukraine energy crisis propaganda that ‘Germans are stocking up with firewood’ heralding the end of the world and peace in our time, only serves to underline the fact that so many Germans enjoy enough space on their property to have a wood burner, a year’s supply of timber, and retain enough space to keep a flock of geese. (Admittedly, not the ones in the beautifully kept social housing apartments. But they have cheap brandy to keep themselves warm).

I loved Germany and the Germans, but I also hated it. Their paradoxical respect for freedom extended to allow you to buy tobacco, vapes, tasers, flick-knives, hard liquor and sex equipment at the checkout counter in almost every supermarket. But it did not extend to you having the right to breathe air on a train.

And only on the train or bus! There were no restrictions on the platforms, or the stations, or on aeroplanes, or in airports, or restaurants, or in any other public setting!

It is a plainly stupid policy, that grated me so badly, I hope never to go back until such idiocy is done away with.

But what I cannot understand is how and why the Germans do this to each other. Why their rebellious youth will shout ‘Communism Now’! and cover themselves with tattoos and get drunk and go to sex shops, and generally rebel against all that is holy, but they sit quietly and obediently on the bus with a face muzzle!

I can’t understand it. The Norse mythology and stupid haircuts are clearly just a substitute. An affectation of masculinity and rebellion, where in fact, there is only defeat.

The people I saw enforce such idiotic rules on each other seemed to be doing so because they had fear in their hearts. But not fear of Covid. Fear of their neighbour. Fear of being different. Fear of individuality.

The teachers at my kid’s school confidently assert that bullies bully those who are different. Their argument is that this is wrong because diversity is our strength. (Who the ‘we’, constituting the ‘our’ is in that statement is something sinister and never explained). They are incorrect. Their argument implies that uniformity could be a solution to the ills of society.

Real solutions lie in decentralisation, not uniformity. In diversity of skill and opinion, not skin colour or sexual orientation.

The people I met on that trip displayed a fear of disunity. I took that to be a sign of fear in general. An indication of a lack of love for the other, or the unknown. An insecure desire for certainty.

Love is the union and acceptance of the other. When we say ‘God is Love’, and that he is a triune God, that is what we accept. Love of the good is to accept the other. Even the stranger.

The superstitious fixate on objects as a cause. Socialism rests on the superstition that those who possess money are morally contaminated. Unerringly, that contamination is not deemed to spread to the ones who will ‘redistribute’ it later on. Or that paper masks keep disease away. Or that totems or idols of political ideologies will bring forth utopia. A culture of cults, the worship of currency, compliance and consensus all seem to be geared toward staving off the outcome of a Grimm fairy tale.

It is evidence of faithlessness.

The working class train conductor cannot stand to see a person walk onto his train, unafraid of illness, and not clinging to a cloth charm. The performance of such an act in public shines a beacon of light that exposes the cracks in their totemic worldview. The rejection of consensus or rules by decree must be made to have consequences, or the social order is shown to be impotent or incorrect.

This cannot be tolerated by people who place their trust in idols like rules, government or ideology. The German proverb that ‘strong fences make good neighbours’ becomes a weapon, not a safeguard. The superstition revealed by the socialist scanning for dissent or disobedience is that it is his perfect adherence to the ideology that prevents the sky from falling, saves the world, and allows the sun to rise again each day.

The Bolsheviks were, after all, the supervisors. They need not fear becoming dictators or bourgeoisie when they take over the feudal or technocratic hierarchy because they have idolised themselves and their team. The collective is king, like the Borg in Star Trek.

Of course, German people are not CCP thugs or Stalinists by any stretch of the imagination. As I said before, they are my kind of people. We are like them in so many ways, particularly that Saxon streak you get by ‘rule-takers’ down in Southern England.

They have no monopoly on such idolatry of the self or one’s ‘team’. I think there was a chap called Moses who noted that you can’t turn your back and go up a bloody mountain for five minutes, without some idol worshipping going on.

I think the German flavour of social oppression comes from their geography.

Sassnitz and Rostock are touristic novelties to the germans who are not by and large seafaring people. The major maritime hub of Hamburg is an obvious exception, but the character of the majority of the people seems to be descended from agriculturalists more than explorers of the high seas.

By Scottish, not American standards, the vast long plains of farmland and forest that stretched between Rügen and Berlin had a curious uniformity of their own. The railways cut in straight lines, on long tracks, through straight countryside.

One can see the patterns of society in the repetitions of land use by train, perhaps better than any other mode of transport. Farmland, forest, suburb, Kleingartens, town, city, grassland, industrial area, residential area. Segregation, boundaries and repetition, repetition, repetition.

Land that has been farmed since the ice age is shaped by repetition, and so must be the people who’ve been there shaping it for eight thousand years. The regularity of seasons. The predictability of a continental air mass. The cycle of crops. The seasonality of the game.

And that land gave life, through the discipline of repetition through those cycles. Culture was forged in repetition and pattern across generations. Predictability and repetition succoured and nourished. It warded off famine, pestilence and strife like a minor deity in its own right.

I can imagine the eugenicists of the twentieth century coming from long lines of people involved in animal husbandry, with the matter-of-fact good-faith pragmatism of a farmer.

And that translated to industry. The endless straight lines of railway sleepers that cut for mile after mile of uniform track, bringing prosperity and progress to build and forge and knit together a nation of tribes isolated by centuries of forest, and feudalism.

As one who started out steeped in the love of tradition, routine and process imbued in the Royal Navy, I can sympathise with respect for repetition. Tradition at its best is memory. The shortcut to wisdom.

And yet, it must not become a false idol.

We must love the other, as much as we love order. And we must recognise human nature for what it is. Idolatrous, covetous and narcissistic. We need to be farmers of freedom, in every generation, because tyranny is in our nature. It seems to grow out of the very ground we stand on, and spreads like fireweed. Again, and again.

Thanks for reading Captain Yankee Jock! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Thank you for reading Captain Yankee Jock. This post is public so feel free to share it.