Apologies for the slight delay in this (last) week’s edition of the blog. I’ll owe y’all one. I have been repositioning a little workboat from the Netherlands to Germany, and we had a few issues with watertight integrity, steering, power, and so on. Turns out engines and electrics don’t like being ankle-deep in seawater.

It has been a bit of a nightmare week (10 days), where it seemed that everything just went wrong. Every day was a long one, but we got there in the end. ‘Arrive Alive’, that’s my motto.I always prefer dealing with physical problems in the real world, to the capricious problems of the social world. Unfortunately, one rarely excludes the other. Everything always breaks, given enough time. Engines are honest that way. People are in a different category.

When I was younger – an apprehensive adolescent – I had a recurring dream for a while. In the dream I was hiking up a mountain path. Hard, stony, and narrow, I climbed for many hours looking only at the steep path in front of me, as heavy pack and sweaty brow occupied my attention.

I came to the top of a ridge and looked out to the west, where a yellow-orange glowing sun filled a wide and fertile valley with a bright and golden glow. It filled me with joy to contemplate the glen full of life and beauty. The remaining hike to the summit felt less difficult, and I could no longer feel a heavy load weighing me down.

When I ascended to the summit, there was only barren rock and the darkness of night. I walked across a flat and empty plateau to a brightly illuminated white field tent. Upon entering, I donned medical scrubs and took position at a conveyor belt. The conveyor belt would bring injured bodies to me, and I performed surgery on each one, before immediately being presented with another. I would perform surgical repairs repeatedly, attentively, and without rest between cases, until I woke up.

This dream was so realistic and clear, and I had it so many times, I can recall it as though it were an actual day in my life.

It is my life.

I took it to mean seriously that the purpose of my life would be to solve the problems that I encounter, as properly, precisely, fully, and indefatigably as I could. That I would have a pause for fecundity and family at a mini-summit, but that in striving upward I could make something useful of myself. And that one day, I might be able to be useful in making things better.

This little expedition has certainly brought me a relentless conveyor belt of problems to solve. So too it seems for the rest of the world.

Last Monday I wrote and published Good Morning before having a lovely conversation with Paul and Tim on the State of the Markets podcast. (Welcome aboard to the fifty or so new recruits from the world of business, by the way). I spent the rest of the day packing my bag and doing all of the last-minute jobs that my wife can’t do when I’m not around. Replacing the kids’ car seat, changing wiper blades, getting salt ready for the soon-to-be regular morning frost on the path, and so on. Pre-emptive problem solving, as much as I can.

I travelled first thing the next morning to Amsterdam, before taking the train to Eemshaven, in the far north-easternmost corner of the Netherlands. I was unexpectedly glad to be in Amsterdam again. I have cumulatively spent several months in that lively city over the years. As a dirty unvaccinated troglodyte, I had long since made my peace with the possibility of never travelling to Europe again. However, the airport and the train station heaved with life and there was not a mask in sight. And no PCR, vax-pass control or coronatarian measure of any kind remained in place. Thank God, nobody seems to care anymore. And as of yet, the traditional bureaucrat still loves the inky wet thump of an actual stamp too much to relinquish it for Uncle Klaus’s mind-reading digital dissent detectors.

Three connecting trains and four and a half hours later, I arrived at a dark and empty train station in Eemshaven, hoping to ring a taxi. As I phoned my third taxi company, it became clear that none were available in this industrial and uninhabited region. I dimly began to realise that there had been no other passengers on the train when it arrived here. By this time, even the train driver had switched the lights off and gone home. Despite false hope on the app screen, Uber did not seem to have any service available either. (I’m now using the ‘Sixt’ app in Germany – highly recommended).

I phoned my hotel, where fortunately the owner spoke decent English. He offered to come and pick me up. It must be bad for businesses to lose guests? He asked if I was at the train station by the ferry terminal. I said, ‘uh, yes I think so’! I could see a mast, and what looked like a ferry terminal building by a main road, on the other side of the car park. I assumed that I would make it easier for him to find me by moving closer to the landmark he had mentioned on our call.

I took three or four steps out of the station toward the ferry, and a large security gate automatically closed behind me. I thought, ‘Wow. The Dutch are efficient’.

After waiting under a streetlamp by the ferry terminal for 25 increasingly cold October minutes, my driver for the evening called me. ‘Where are you’!? says he. ‘I’m by the ferry terminal, neon sign, big anchor, main road, etc’, says I. ‘How did you get there’?!

I walked back to the train station where his car headlamps were the only visible sign of human life for miles around. I now realised that the marvellously automated security gate did not want to re-open automatically. In fact, I was now locked into an unmanned ferry terminal, enclosed by a ten-foot-tall spikey fence and barbed wire. There was nobody to assist, no guard to call, no gap to crawl under, and no opening in these bloody well maintained Dutch defences.

Not being a fourteen-foot-tall Dutchman myself, it took me a while to figure out a way over this obstacle. I climbed first onto an adjacent smaller fence and perched there, as I strained to lift my two 20 kg sea bags over the spikes without ripping them open. I was careful not to lose my grip, and flatten my near seventy-year-old driver, as he caught my bags on the other side. Then I bundled up my jacket to cover a portion of the spikes, where the gate mechanism joined the fence provided a gap in the barbed wire. This is where I gingerly placed my testimonials, before passing over to the other side and sliding down the railings.

‘Arrive alive mate’, I said as my driver laughed and introduced himself as Roddy (or Dutch equivalent). ‘At least you have a good story now’ he said.

The ship did not arrive the next day, as scheduled. She needed a ‘quick repair’ before crossing the English Channel.

This inevitable sign of things to come did not dampen my spirit at all, as the delay afforded me enough time to explore the thousand-year-old metropolis of Groningen. It is a beautiful city. So clearly built by seafaring and trading people, with its Hanseatic and exotic influences, medieval guild culture and craftsmanship at every turn. The philosophy articulated by that formidable southerner Hugo Grotius in the Freedom of the Seas, Groningen had been exercising for centuries prior.

What fascinates me as a trained Marine Spatial Planner and seafarer is not just the clear nautical influences. The huge frameless and clear picture windows at street level on every building (desirable after centuries of toiling below deck and the scanty vitamin D supplied through a porthole). Or the eight-foot tall doorways and ample headroom afforded everywhere (as a response to tall Dutch folk who’ve been banging their head on beams and deckheads for generations). Or the excellent hygiene and tolerance for smoking, narcotics, alcohol and sexual depravity of every kind (accepted without fetishization by a realistic seafaring race, used to travelling and living cheek by jowl in naked honest discomfort with their fellow citizens, in their worst moments of weakness both afloat and ashore). Or the readily apparent mastery of all forms of craftsmanship and engineering in the built environment, from canals and bridges to tiny architectural details, like hand-painted tiles on window sills and neatly decorative accessible plumbing (only people who take responsibility for the future maintenance of their buildings at a deep philosophical level can create such simultaneous beauty and pragmatic utility).

Nothing is standard in a city like Groningen. Every building in unique. There are no imperial or neo-imperial (metric) measurements in the built environment, and everything fits so perfectly well together as to seem magical. The width of doorways, the narrowness of spiral staircases, or the angle and hue of joints determined by what could be achieved at the time of creation and later maintenance, by the nutrition, learning, and skill of the Dutch people. By the size of their bodies, the dimensions of their Meister’s handmade tools, and the sweat of their brows. The love of hard-wearing but beautifully painted tiles speaks of countless long days sweating on docksides, or toiling in and alongside wet and muddy canals in perpetual dampness, salt and soil.

All of that is evident and unsurprising, if inarticulate, to most seafarers who come to the Netherlands.

However, what is most striking to me about the built environment in the Netherlands is their attitude to boundaries, and what it says about their culture and philosophy.

The clear and strong boundaries exemplify the Germanic proverb that Strong fences make good neighbours, perhaps far more so than in Germany today. Only very well-constructed buildings and streets can allow people to share walls, apartments and infrastructure in a city enclosed by canals and walls for untold centuries. Only the Dutch protestant understanding that churches should be closed through the day, because God has given you a divine calling to your work, and he is present in your labour, can produce specialisation of craftsmanship to this degree. And only the mercantile spirit can pay such good attention to the art of accountancy and finance to ensure this treasure of a dwelling place is kept suitably maintained, yet properly priced. This means future descendants need not start from scratch, nor sacrifice too much, yet still, they must strive.

Back in the far more recently constructed post-war and C19th villages, I passed through between Eemshaven and Groningen, the same philosophy is made clear in other ways. Residential homes sell garden produce, from a stall with an honesty box in the front garden. The municipal bus stop sign is enclosed within a private front garden. Commercial buildings have permeable or minimal boundaries and lie adjacent to residential buildings. There are few (or none I could see) of the awful 1970s Semi-Soviet mandated ‘community’ centres that are sanctioned and poorly maintained in British towns. Almost zero graffiti. In both town and country, the paving consists of tiny brick tiles, so that the path can settle unevenly over time, without the hazardous cracks of large concrete slabs. Apple trees are pleached to avoid intruding on a neighbour’s land. Strangers are greeted politely in the village with the same trust that allowed me to travel the entire length of the country with nobody checking my train tickets. There seems to be little fear of disease, or of a stranger.

In the Dutch spirit, there is conscientiousness, discipline and orderliness, certainly. But this is philosophically balanced with openness, trust and consent.

There is no superstitious or Marxist boundary between commerce and life in the Kingdom of the Netherlands because one is central to the other. There is no physical space between neighbours, as there can be no spiritual space for prohibitions based on resentment between neighbours. Not if each is fulfilling their own calling to what is highest, on their own route, down a shared path.

No central planner could ever come up with the efficiency of a city like Groningen. If you squint through the sunset-bathed outdoor café bars that line the canals, you can almost see the ghost of the archetypal Dutch merchant who built this city and this culture.

He rests at home with his large family doing domestic chores by the light-filled picture windows and watching every neighbour, trader, friend or foe come and go through the day. They watch their windows like an analogue eBay. The ticker tape of the day, that allows communication in both directions, so that no opportunity is missed as one’s network refreshes in the heaving streets outside.

And what if opportunity knocks?

The merchant is dressed and ready. He must be, as from the moment he wakes, every passerby can look into his home. He opens his door directly onto the street, where no doorstep, fence, garden or wall impedes him. He is at once available to the world of commerce. The street between his home and the canal is a quayside, warehouse, trading floor and marketplace open to wholesale or retail. The owner and decision maker himself, immediately present. The tools of property rights, communication and currency are fully available to every free citizen. The public square is the trading floor, helpfully lined with cafes. It is also, therefore, a mess deck. The efficiency of the use of space is a marvel, that facilitated a hyperlinked society.

(Of course, you cannot discuss maritime trade or commerce without discussing morality. the local (and beautiful) maritime museum of Groningen understandably has its own slavery exhibition. I thought it a much more honest one than my recent visit to Liverpool’s version. At least they admit that until English protestants convinced them to end slavery they had been happily accepting the status quo. Internationally, until the Royal Navy enforced a global ban, and domestically a few years later.)

God made the world. It took the Dutch to build Amsterdam (and Groningen), as the saying goes.

Christians are encouraged to become wealthy, so long as they come through Christ first. This means that the getting of wealth should be done with honesty, integrity and with one’s own skin in the game. Not by the sacrifice of others, or the hi-jacking of their pension funds and tax dollars by ESG driven ideologues. Giving to the poor is a fundamental requirement of the Abrahamic faiths. Therefore, it is not incumbent upon a follower of any of these faiths to be poor.

Be not afraid. That is how the Dutch culture raised such wondrously beautiful cities, out of featureless uninhabitable swampland on the edge of a continent.

My little ship arrived at midnight and I met my new deckhand at 5 am the next morning. Voyage preparations were scant, so the entire morning was occupied with putting a passage plan together and loading fuel before sailing. Even in this industrial harbour, the Dutch had found a strip of green land next to our berth suitable for grazing. Sheep wandered up and down a perfectly linear field and stared at us indifferently through a chain link ISPS code fence.

Our destination Cuxhaven, Germany, for Kiel the next day.

Although I didn’t see it, and have never been, we passed Heligoland. This now German, formerly Danish and British, Frieslander territory in the German Bight is historically known for providing marine pilots for ships trading in the Hanseatic league. The local tourist board calls it the Holy Land.

It struck me, that in those bad old days of shipping, those pilots would have climbed on and off passing ships using the good old Jacob’s ladder. A common rope ladder you might have seen at a children’s playground before we decided that children were Humpty Dumpties in disguise.

When I worked on the Panama Canal for a project, I learned that the modern Pilot Ladder was invented by a couple of American-Panamanian marine pilots, as a distinct safety improvement, on the busiest canal in the world. A specified height limit, rope diameter, shackling point and so on, guarantees a level of strength. Spreader bars and man-ropes provide stability while climbing. The bottom steps are made of rubber, to prevent crushing, and so on.

Those pilots tried to act like Jacob’s ascending angels, or Volvo’s seatbelt marketing department, and gave their patented design to the world International Maritime Organisation free of charge, and without expectation of royalties. In the name of safety standards for the greater good. How many lives have been saved by this action will never be known. Although many lives are still lost at sea due to improper use and failure to maintain these ladders.

To be a seafarer is to be part of the commercial lifeblood of humanity. It is also to be part of a history. One that lays claim to being the second oldest profession on earth, with cave paintings of canoes as evidence that as soon as prostitutes were invented, men needed boats to get to them.

My first time passing through the Kiel canal the next day was then of great significance to a history lover like myself. However, for risk of defamation, I cannot go too deeply into the details of my transit. Needless to say, all did not go to plan!

My gormless deckhand, (allegedly a 200 GT Yachtmaster with experience as an instructor – get your money back chaps), informed me that the repairs effected in the UK had been holding up alright so far. This was evidently tosh, as my first passage from Eemshaven to Kiel required four engine restarts and ended up with me arriving in darkness, with reduced speed and steering.

Engine checks the next day were ‘OK’, he said. Being ignorant of this type of check, I had to accept his word for it in my hurry to get through the canal. I departed the locks at Cuxhaven in darkness and arrived at the locks to Kiel, at Brunsbuttel, by mid-morning. Engine alarms and steering defects were apparent from the get-go. As was disobedience from the crew.

Disobedience would come to the fore, when my deckhand turned off his radio, and did not wait for instruction regarding mooring ropes. Before I knew what was going on, my deckie had let go of our ropes too early. My 25 Gross Ton aluminium workboat was now being thrown around in the locks like an empty can of Coke by the engine and thruster wash from the big ship departing the locks before me! And my steering on the starboard engine – obviously – picked this precise moment to disappear.

So before I knew it, my ship had turned 90 degrees to starboard, and I had no ability to turn to port to correct it!

Within thirty seconds I was facing backwards.

Backwards, in case you were wondering, is the wrong way to be facing if want to transit the Kiel Canal!

Panicking, mortified and steering with extreme difficulty, I managed to proceed three-quarters of the way out of the lock moving astern, steering with my one good engine backwards. Realising the ship was slightly less rudderless than the deckhand who assisted this situation, I decided to bite the bullet and attempt a 3000-point turn to starboard. Like that scene from Austin powers with the golf buggy, I eventually managed to bounce my way around to facing forwards, just in time to narrowly avoid a collision situation with the ferry service that passes close by outside of the locks.

After a long day, and only being reprimanded for speeding and improper overtaking a couple of times, the passage via this beautifully constructed and well-maintained military canal otherwise went well. My stress levels returned after dark, however, as my illustrious deckhand refused the help of shoreside line handlers, didn’t listen to instructions, and somehow managed to cast off the boat without himself on board.

This left him standing on a floating wooden fender inside the Kiel lock chamber, with no means of escape, and with three big ships and a yacht moving around in the basin on departure. This helpfully added what seemed like 100 years of me thrashing around trying to ‘walk her in’ parallel back to the fender he was standing on.

Ships without thrusters are designed to move forwards, not sideways. With bent and broken steering, no thrusters, a ticking clock, lots of witnesses, and a crewman exposed to crushing and drowning hazards, coming back alongside in a confined space after the wind has blown you off is not an easy or pleasurable experience.

After a fraught berthing in Kiel harbour, a kebab and a short night in a hotel, we set off in early morning darkness again the next day for our long passage to Sassnitz, Germany. And again, despite corrective instruction, a departure briefing about mooring, and the lessons that should have been learned the night before, my deckhand almost got himself left behind on departure! Again!

A few other ‘unreportable’ offences added up to me advising the vessel owner ‘Do Not Rehire’, before sending the utterly defective man back home to Ireland.

They sent me a big rough and tumble Geordie lad instead, who is green, but keen, which makes all the difference.

Anyway, when we got the technicians out to look at the engines, it turned out our compression seal had gone, and we were slowly sinking.

I don’t understand German beyond my half-forgotten two years of High School Standard grade, and a little trip to the Black Forest when I was 14. Perhaps the engineers among you would have understood the ‘Grosse Sheisse’ utterance from the engineer? Something to do with the fact that electrics don’t like being ankle-deep in seawater for very long?

We pumped out the bilges as best we could, and kept the pump running as we took a seven-hour steam back west to Rostock. The boat is now out of the water, and I can see why my steering didn’t work! The starboard prop is stuck at 25 degrees off centre. Not helpful.

A few days in Sassnitz, and now in Rostock have been lovely. However, this being former East Germany, there are still some troubling signs of a culture in trouble. And that was aside from the fact that Sie Germans are the only people in Europe still clinging seriously to mask mandates. (Which in itself, is freakish and shocking when you’re an outsider looking in).

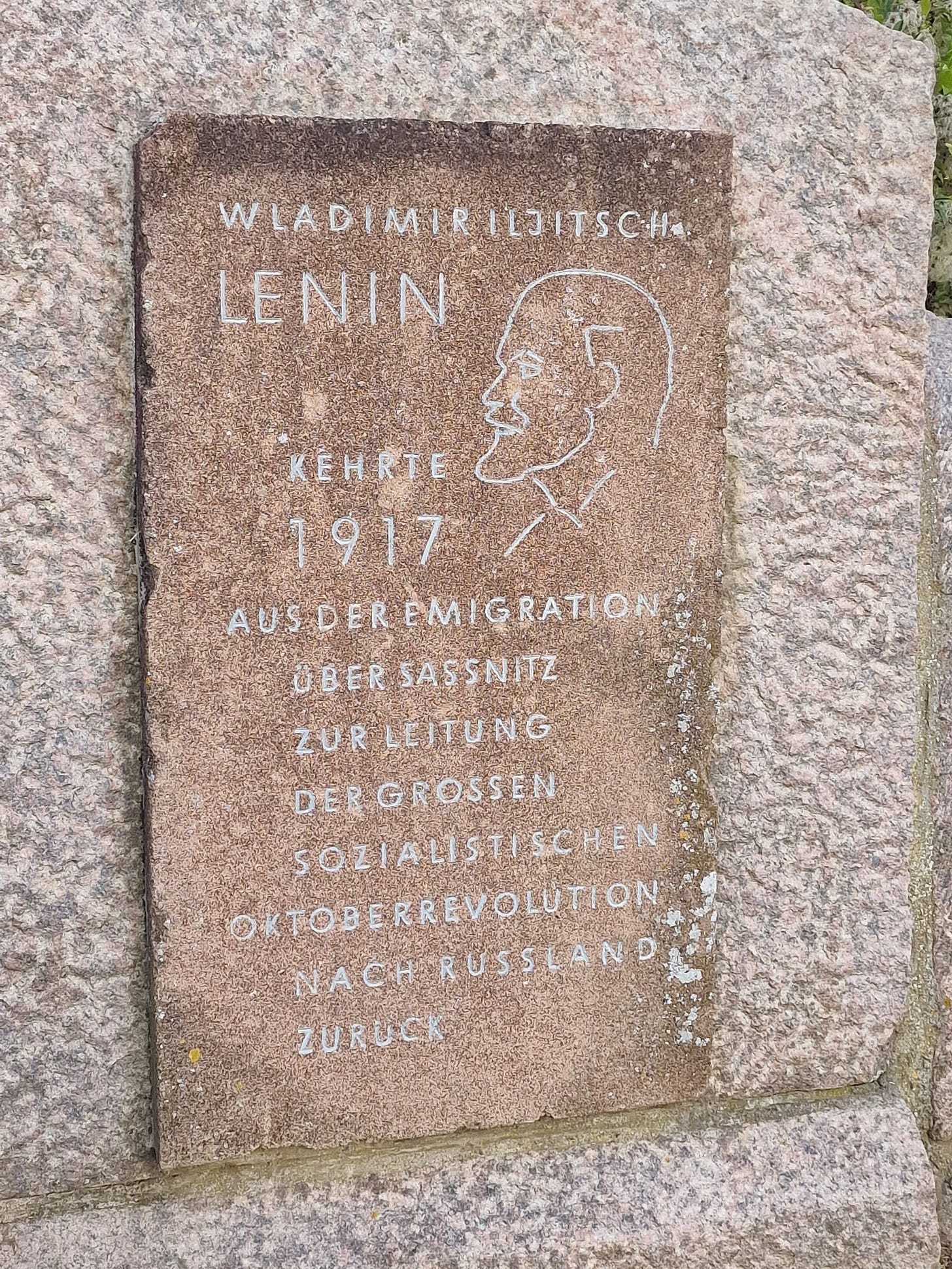

Like my time in St Petersburg, I noted with slight bemusement the Che Guevara T-Shirts and Communist military hats on sale at tourist souvenir shops. The alarm was raised further, when, from the corner of my eye, I noticed a discreet yet well-maintained monument to Vladimir Lenin and the Russian ‘October’ Revolution. Apparently, Lenin sailed from Sassnitz to Sweden on his return to Russia from exile in Switzerland, and some locals are still rather proud of that fact.

Unlike in the Netherlands, in the former East Germany, I have noticed quite a lot of graffiti. Much of it is in English, sporting the ‘ACAB’ – All Cops Are Bad export from the (thoroughly covid-safe) BLM riots and resurgent radicalism in the States in recent years. I saw ‘Communism Now’! with a hammer and sickle spray painted suspiciously near the University of Rostock today. You know, between the Starbucks and the Zara outlet stores doing a roaring trade just off campus.

Sassnitz itself is beautiful. A former seaside resort for the Kaiser and other 19th Century gentry, it has grand buildings and well-maintained public spaces. The fishing harbour is a popular tourist resort, and the private properties are large, well-maintained, and fronted by the type and number of automobiles that suggest affluence.

So why the carefully preserved respect for murderous socialist leaders? I mean, if you’ve ever read any of Lenin’s work, it’s is plainly utter guff. The verbosity of a genocidal Russel Brand, combined with the narcissistic certainty and blind assertion of Schwab and von Der Lying.

Masking on public transport provides a clue.

My default rule on masking varies when travelling on behalf of another company. If I’m by myself, I don’t care what the law says, I’ll play stupid foreigner and just not wear one. If I’m travelling for someone else, I’ll wear one if asked.

So in the few days travelling by train between Sassnitz where the boat is and Sagard where the apartment is, I did not wear a mask. After a few days without questioning, I started to wonder if the Germans really are so compliant that they will follow stupid rules, even when they are not enforced? What’s going on with their national character? I contemplated Steven Wilkinson’s Pitchfork Papers’ recent piece on German culture, entitled ‘Mittelstanding Together’.

After a few days, I thought, none of these [male] conductors has said anything to me. Maybe it’s something to do with me being a six-foot-tall Skinhead of a Scotsman, stinking of saltwater, sweat and Whisky at the end of a long day on the boat?

Then there was a female conductor. And she didn’t have the slightest hesitation in shouting at me, or my giant, effing and jeffing Geordie companion.

Women are always the worst bloody socialists. The first day of the Russian Revolution kicked off with International Women’s day. The little nag-Nazis who handed out white feathers, and sent young boys off to the trenches, to be maimed or killed, rather than face the social hellscape that would be theirs if they dare displease the womenfolk.

Another great benefit of the acceptance that comes from being happily married to a beautiful woman, with beautiful children, is that I do not need one jot of social approval from anyone else. Male or female. That is the superpower of love, that young people who forsake marriage are giving up.

Invincibility.

The persistent idea that social approval or that consensus equals virtue and truth is a serious danger to humanity. It is antithetical the Christian or rational morality.

Christians, after all, are to live like Jews. However, they are prohibited from using their tribal identity or rank in the social hierarchy as a source of authority.

That is why the coverage of the appointment of Hindu PM Rishi Sunak has so confused commentators like Trevor Noah in the US. America is a Godless, secular republic. It is not a Christian Kingdom, where the monarch is subject to the law of God before any people are subject to him.

It is notable that the Netherlands is also a Kingdom, and that by polling, the happiest countries on earth are consistently all constitutional monarchies.

Is it a problem in an expressly Christian country that our PM is a Hindu? No. He is a subordinate deity, in the bureaucratic polytheism. Subordinate to the King, who has a role, that is subordinate to God. God is and must be a personal God, simply so that no human can imagine that it is they who are God, as is our masonic proclivity.

We see divinity in the strong boundaries in the built environment of a city like Groningen. It is visible in the accumulated outcomes of thousands of generational iterations of voluntary dispute resolution and negotiation. The craftsmanship, hygiene and orderliness have beauty because they speak of the love of forebears for their descendants, and for their love and acceptance that there is a possibility of revelatory truth that make problem-solving a worthy practice for a partially divine creature.

Federal Republics, like the US and (some small corners of) Germany, seem to lack the attention to detail that should be present in a properly functioning Kingdom. Most likely because bureaucratic polytheism has no God above the technocrat at the top. Therefore, the Good is not discoverable by revelation. It is only decided by Fiat, either of the majoritarian Mob or the Vanguard classes.

King Charles’ accession foreshadows the end of the monarchy, sadly. As a sovereign, he is our example of sovereignty, and God’s sword arm and beacon earth. However, as a WEF globalist, he is a contradiction to that idea.

His activism speaks of the same flawed idea that Lenin had. The idea that underpins the flawed thinking of all political ideologies. That there is a class of human that is different from others. That is exempt from the rules that apply to others. That can, and will, walk all over morality because it this they who decide what is moral.

National Socialism, International Socialism (Communism), Fabianism, Technocracy (an actual religion for those who don’t know), Leninism, Stalinism, Maoism, etc, all share this original false premise. They are all slight variations on the mechanism for the delivery, of the same evil outcome. The only thing up for grabs in their sinister competition is the identity of this Vanguard Class.

It is our King’s vanguardism that is a performative contradiction. That contradiction endangers the constitutional balance of the United Kingdom by its mere existence.

Brexit, receiving the blame for all our current political woes in the Spectator these days, was necessary but not sufficient. Necessary because the EU is a false idol and a Godless philosophical tyranny. Insufficient, because our own bureaucratic class is also a narcissistic cult with the same contempt for its population.

Vanguardism, Fabianism, Leninism, Trotskyism, Fascism, Socialism and dare I say Republicanism are all variants of the same conceit. That there is no absolute universal morality that is discoverable by attentive problem-solving, work and negotiation. Rather, all is decided by the power of the will.

This axiom leads immediately to the idea that the identity of the highest authority is up for grabs. Hence the fuelling of narcissism and cronyism in modern politics and corporatism. The intellectual narcotic of political and economic theory that rejects reality at all costs, to ensure the benefit arises to oneself or one’s group. It is the rejection of eternity or universal morality as a concept.

The ladder between heaven and earth is present all the time, in everything, everyone and everywhere. You can climb that ladder if you notice things about the world around you. Your work is to infer the highest operating principles from your empirical sense observations. The angels ascending and descending Jacob’s ladder in the book of Genesis are the invisible connecting thread between you and the highest, eternal, universal and permanent aspects of Truth and revelation. The mathematical principles of being that we must decipher, rather than decide.

The trust that builds a society, is the trust that all human beings have an instinct that can be exercised to climb Jacob’s Ladder. And that the ladder is always there.

Our leaders do not believe this, and they do not trust their own ‘people’. As a leader of flawed human beings, operating in difficult circumstances, I can sympathise. But there are some things too important to be left to a political and bureaucratic class, who believe they are exempt from making mistakes.

The origin of good leadership, which is the pre-requisite for decentralised command, is the understanding that the Captain is sometimes wrong. Only by teaching everyone to climb the ladder, can the feedback of improvement begin.

The fear of God should be the fear of doing irreversible damage to this world that is not immediately apparent until future generations come to cast judgement of their forefathers. That is the dark side that opportunity cost, political expediency and original sin share in common. Acting in the assumption of perfect knowledge and the creative-destructive power that we possess, but with acceptance of the deep limitations of humanity.

All political theory is conceit. The philosophical technology that provides a defence against it is religion. Therein are the natural hierarchies of biology, family, competence, specialisation, negotiation, and self-defence.

The Tory party is now simply an epithet in Scotland. It means a group of people who are only interested in the promotion and preservation of existing hierarchies beyond their natural existence, using the power of the state.

A real conservative party would be one that conserves and protects the natural hierarchies from the artificial hierarchies of politics. Not one that promotes the same dysgenics and socialism as its ostensible political enemies. The modern Conservative party is a vanguard party, as much as the rest of them. Let Rishi Sunak be the one to tear it down if he can.

But that would require a humble reckoning with the idea that it isn’t just bootstraps all the way down. And that your group identity or hierarchy is not the source of morality, any more than anyone else who is seriously trying for the Good.

Fear of disunity is a sign of fear in general. It is a sign of a lack of love. Love of the Good is to accept the other. That’s what these poor misguided German and British socialists share in common. A lack of trust and a general fear of their fellow human beings.

And who can blame them? Looking at recent events like Brexit, without a supporting historical context that incorporates philosophy can only lead to shallow conclusions.

The love of order more than people. The scanning for dissent or individualism, and the intolerance of disagreement with vanguard orthodoxy is terrifying to those whose world begins and ends with magic words by people like Lenin. People who justify evil as ‘necessary’, on the logic that imagined or enforced consensus equals truth.

Any sign of deviation from a manufactured consensus, like a maskless man on a train, is a glaring beam of light shining through the cracks in their worldview. If this maskless heathen does not value social uniformity above his own life, then the vanguard does not speak for him. Then there is no consensus. Our worldview is not moral.

Easier to demonise or shout at the dissenter, than to examine our own support of immoral ideas. Easier than re-examining the Marxist fetishization of money. Where somehow the absence of owning money makes one moral and justifies violent ‘redistribution’, yet when redistributed to solve all social ills, does not somehow spread its immorality. Where nothing needs to change, except who is at the top of the pyramid. Where the corporations are the unholy symbiotes of the state, and the only marketplace is the market in force.

The old threat from armchair historians when I was growing up (and more recently in the USA) was: ‘’you’d all be speaking German…’ doesn’t seem so bad anymore. In fact, I don’t think we’re very dissimilar.

When I look at Eastern German problems, I see a lot of the UK and the US in them. And in their common political problems.

I think the truth is, we all lost the war. And we’re still too traumatised to imagine a better way of being.

Thanks for reading Captain Yankee Jock! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.