Whitby is an amazing place. Its scars and memories are on display. Its heroes remain alive.

We sailed past Lindisfarne to get here, but this is Northumberland. The kingdom of Vikings, where peoples are known by their distinct identities, changing tribal monicker as you progress down the coast. Geordies, Sand-dancers, Makems, Smoggies, Monkey-Hangers and Ringers. People from Whitby are known as ‘Woolly Backs’. Nobody can tell me why, but the bear-like stature of some of the local fishermen may hold a clue.

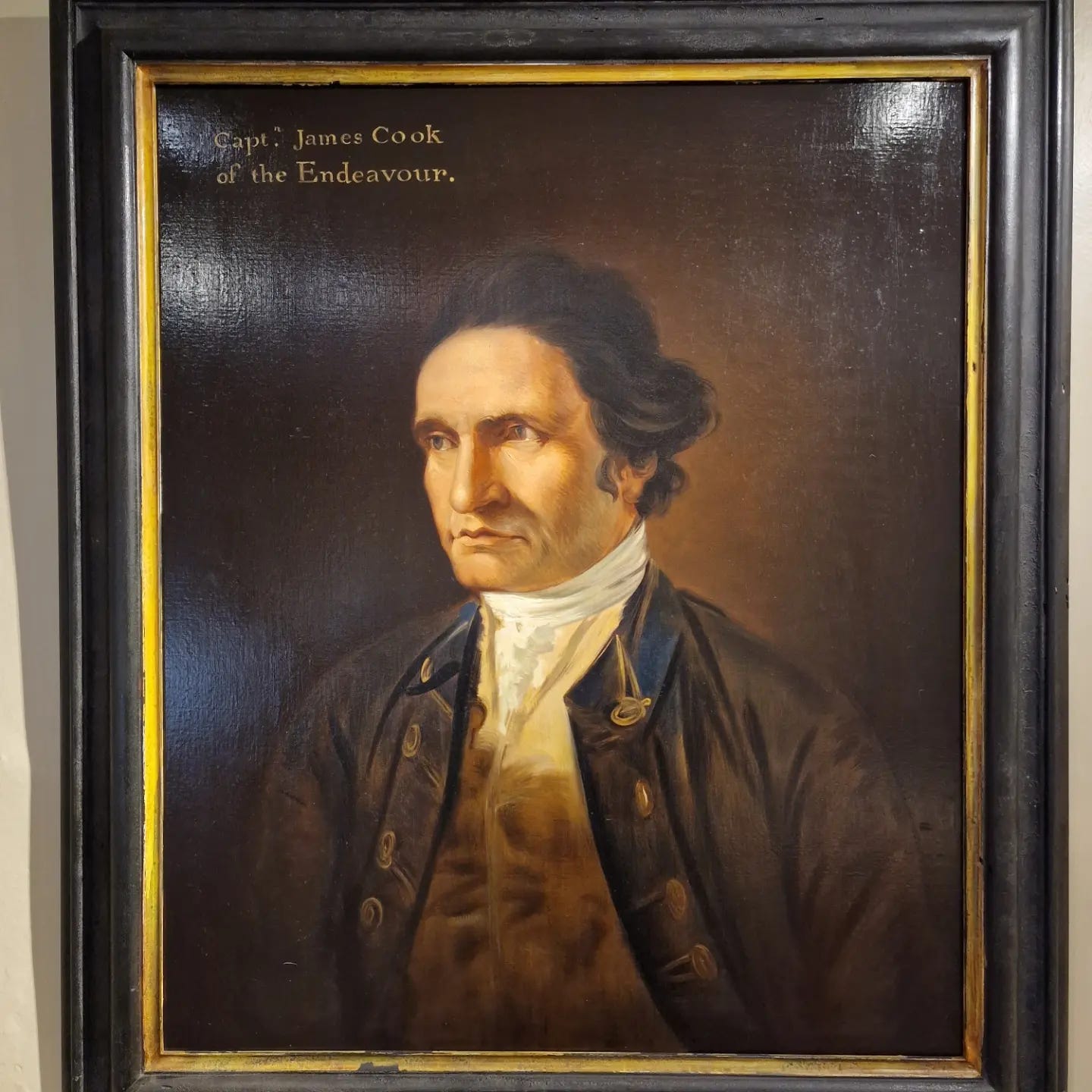

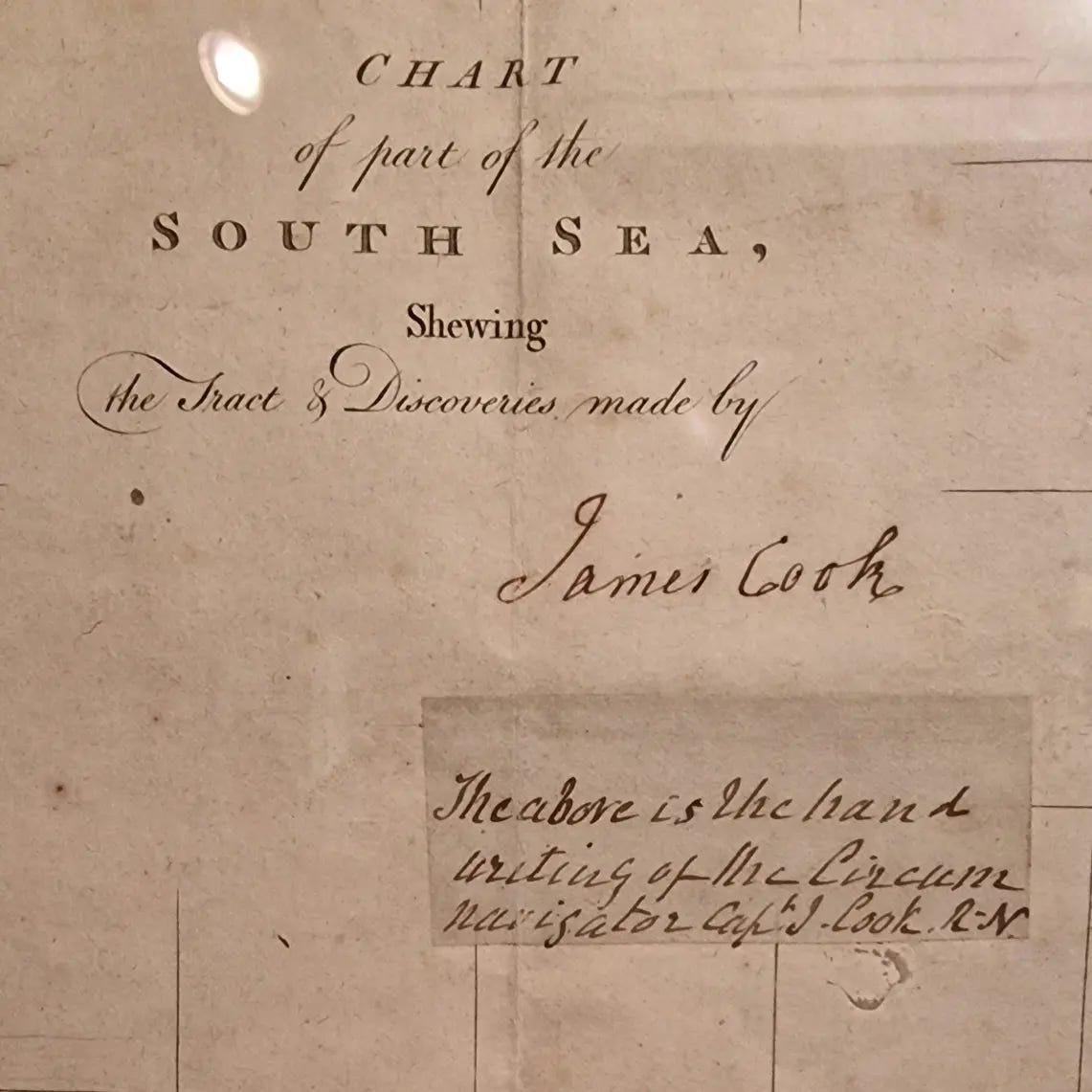

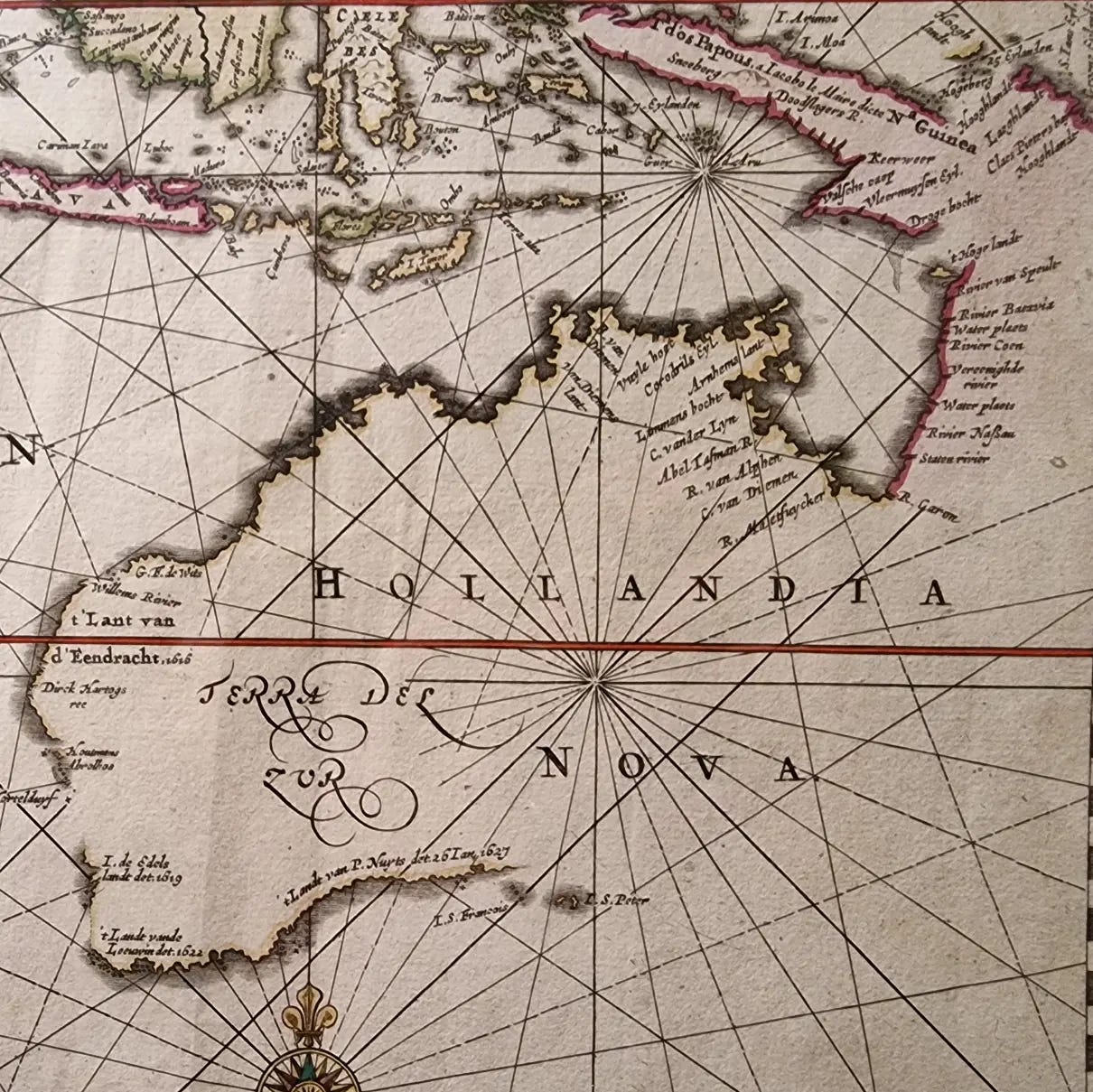

Whitby’s most celebrated resident was Captain Cook. The man who mapped the bit of Australia where almost everyone in Australia now lives. He was quite the man. Being from Staithes, he was a ‘Ringer’. The local Captain Cook museum is based in the former home and shipyard of the quaker family that tutored him during his nine-year apprenticeship on merchant ships. Its collection of artwork, charts, model ships and artefacts from Cook’s life and expeditions to the Pacific, Indian and Southern Oceans are truly beautiful.

The exposed brickwork floor in the kitchen where Cook would have dined during his formative years evokes images of a different time but of real people.

When Cook was apprenticing here, the Jacobite rebellion had not yet been quelled, the American revolutionary war and the French revolution were decades away in the future. When he went to sea, the sextant had not yet been invented. When Cook encountered ice in the Southern Ocean, he postulated the existence of Antarctica, but nobody would actually get to Antarctica for another fifty years after his voyage.

A lot can change in 250 years. But, overlooked by the ruins of Whitby Abbey, Cook would have been well aware of the passage of time.

This land, where the river Esk meets the sea, has been occupied for at least 3000 years. Saint Hild was born a Pagan and an aristocrat. Baptised on Easter Day in 627, she founded the Abbey here in 657, in what was truly still Pagan territory. The Abbey stood proudly above this busy medieval harbour. Its location and reputation as a seat of learning made Whitby Abbey famous throughout Europe, and various royalty were known to visit. With King Oswiu of Northumberland’s patronage, Saint Hild turned many pagans away from the old ways of idol worship, sacrifice and witchcraft.

Abbess Hild expressed faith visually and materially, through art, the poetry of Saint Caedmon (the first named poet of the English language), dressmaking, and the ornate carving of crosses. She integrated Celtic Britons and Saxon culture, at a time of shocking cultural upheaval, centuries after the Roman rule of Britain ended, the Christian world centred in the East, and a foreign speaking warrior elite showed up on these shores. This is where the Angles defeated the Pagans of Britain, and where they met the Saxons.

In 664, church leaders gathered here for the Synod of Whitby, to agree on the methodology for calculating the date of Easter. It was a showdown between the influence of Northern Celtic Christianity and the northernmost reaches of Roman Christianity.

During the debate, the Celtic and the Roman viewpoints were discussed. The advocate for the Roman method argued that Saint Peter was literally given the keys to the kingdom of heaven, which were kept in Rome. In Matthew 16:19, Jesus says ‘I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on Earth shall be loosed in heaven’.

Since both Celtic and Roman Christians agreed on this point, King Oswiu decreed that the Roman method would be used to calculate Easter from that time on. The authority of Rome would be given cultural primacy over the Celtic church thereafter.

I wonder if this moment sowed the seeds of the anti-orthodox schism to follow, that has troubled our notions of authority ever since?

A couple of centuries went by before Ivar the Boneless and his brother Ubba raided these shores and destroyed the original Abbey, in 870.

The Vikings apparently slaughtered all of the Angles who lived here, and destroyed the entire settlement. The Anglian place name Streaneslach was replaced by the Danish name Whitby. The East coast of England is full of these Viking colonies, all ending in the old Norse word for a town – By. They were city-states under the Danelaw, with their own municipal regulations, or By Laws. Whitby, Derby, Thornaby, Willerby, Grimsby, Danby, Hemsby, and a great many other small towns in this region all have the same origin.

The Britons didn’t invent colonisation, but they were intimately acquainted with the concept.

It was the Normans who rebuilt an Abbey here, when a soldier of William the Conqueror called Reinfrid visited here while ‘Harrying the North’ in the terrible winter of 1069. Reinfrid was so overcome by emotion when he saw the Viking devastation of Whitby Abbey that it caused him to lay down his arms and become a monk. He resettled the site of Whitby Abbey in 1078, only to be forced to flee inland after continuing Viking raids.

Despite the amphibious assaults, the Abbey was rebuilt in the Norman fashion, with the support of William De Percy, who later died on Crusade in the Holy Land.

The Gothic ruins that we can see today come from this time.

I am used to ancient things, having grown up playing on the Broch and standing stones at Callanish in Lewis. But there is something truly astonishing about these 1000-year-old stone walls.

They were built here on the western edge of the world, in an age that we can barely reimagine with the help of Tolkienesque fantasy. The schism between Roman & Orthodox Christianity occurred about 25 years after this phase of construction and would have been within the living memory of the builders. That was before the first Crusade. Before the fall of Constantinople. Before the scholars fled back west, bringing the lost knowledge of the ancient Greek philosophers and the occult that had been contained in Constantinople. Before those ideas produced the renaissance. Before the corruption that drove Luther, and before the printing press revolutionised the world.

Something still stands here, and is still beautiful, after all that.

Having arrived by sea, entering at the lowest point of any town, your gaze cranes skyward. The whole town is pleasantly contained by the umbrella-like complex of the Abbey, the stately home of the Cholmley family who took over the Abbey after Henry VIII suppressed it, and the farmland with horses that mark the boundary with the town that lies below. St Mary’s, a later church with a castellated silhouette, provides the comfort of a sentinel.

The Abbey is above what is below. It exudes hierarchy and authority.

As you ascend the 199 steep stone steps from the shoreline to the Summit, you feel the solidity of the architecture and buildings bequeathed by generations of real craftsmen, who didn’t believe in doing things by half.

You very quickly see the inspiration for Bram Stoker’s Dracula, as you follow in the famous author’s footsteps.

Legions of worn and weathered headstones cover the headland. Many of the graves lie empty, and the stones stoop forward. They are looking out to sea for their missing occupants, as their grieving mothers and widows once did.

Cloud and fog roll by, and you travel through time. Your mind’s eye visualises the coffins resting on the benches at each landing, as good Yorkshire folk follow the protocol of generations.

The ruins speak of the race of giants buried in our land, and of the life everlasting.

Permanence is temporary, the worn-out stone attests to that.

A small coffin, carved from a single piece of stone lies unmarked and inconspicuously at ground level, at the south-easternmost corner of the Abbey.

Who’s grave is this?

Will he return to it?

The Abbey, the museum, the English Heritage guidebook, Wikipedia, google, and the local tourist desk provide no information or even any mention of this enigmatic monument.

There is no trite speculation of a memento mori. No acknowledgement at all.

A mystery that captures the imagination.

The story goes that Abraham Stoker stopped in Whitby at the suggestion of one of his most famous stage actors, after a long and exhausting tour of Scotland. The Irishman, who managed London’s Lyceum theatre, had a week by himself before his wife and baby would join him at his seaside hotel.

Stoker walked around town every morning, meaning that he undoubtedly visited the Abbey several times.

It is easy to feel the effect that looking at the empty graves of drowned sailors, and this abandoned monolithic coffin, would have on a weary and lonely traveller.

Stoker is reported to have spent time in the local library, where he happened to become fascinated by a seventy-year-old book, written by a fellow Irishman by the name of Wilkinson. Not Steven, but William Wilkinson (Any relation?), who had served as British Consul to Wallachia & Moldova, in Bucharest. The exotic eastern frontier, where ancient Christendom had dissolved and struggled on the battlegrounds of Ottoman conquest, after Constantinople, and through to modern times. A place where blood feuds still linger, and centuries of enmity are still palpable today. Legends of vampiric aristocrats were long established in those faraway mountainous boundary lands.

Stoker made notes, as he was captured by the story of Vlad the Impaler, and the drama of the Wallachian (modern Romanian) language.

Vlad was known as ‘Dracula, the Son of the Dragon’.

On the 08th of August, 1890, Stoker noted: ‘Dracula, in the Wallachian language means The Devil. The Wallachians at the time used to give this as a surname to any person who rendered himself conspicuous by Courage, Cruelty or Cunning’.

His inspirational trip to Whitby, and seven further years of study and writing, produced the novel ‘Dracula’. Initially written for the stage, the aristocratic actor he chose to play it recoiled from the work and refused to act in it ever again. Unsuccessful in the theatre, the book was a hit, and remains a bestseller to this day, attracting multiple iconic adaptations for the cinema. It is available for free as a pdf download, but it is 400 odd pages. Therefore, I downloaded the 90s film adaptation, starring Keanu Reeves, of Bill & Ted &/or Matrix fame, depending on your age. There is also a new movie adaptation coming out on August 11th this year, which focuses entirely on the nautical element of the book.

The way that a Romanian aristocratic demon transported himself to England, was, fittingly for 1897, by sea. A chapter in the book, which I haven’t yet read, is based on extracts from the captain’s log. The vampire, who represents the negative spirit of the modern age, and the undying evils of a perverted aristocratic leadership, must sleep in the native soil of his homeland in order to renew his powers. Like the feudal lords who drew their power from land, colonies and serfdom. I don’t imagine the poor skipper questioned the unusual cargo of boxes of soil & silver. The money of Princes, and the source of their authoritarian power.

The voyage is disturbed by the disappearance of crewman, after crewman. Count Dracula picks off the entire crew at night, one by one until the Master is left alone on board, and tied to the ship’s wheel before it is run aground and shipwrecked on Whitby Rock.

Dracula shapeshifts to animal form, disguising himself as a black dog, and running up the 199 steps to hide in the graveyard at Whitby Abbey. A powerful image, illustrating the tendency of agents of deceit and falsehood to feign loyalty, use their elevated position in society, and the virtue of institutions to veil their sins.

The ship ran aground on the 08th of August, the day that Stoker found the name Dracula, in a book in the Whitby public library.

Fifty years prior to Abraham Stoker’s Dracula, Karl Marx published his Communist Manifesto, in London. Both authors note the injustice of the privileged classes who were the inheritors of the benefits of feudal rank. The difference is that Marx wanted a violent return to feudalism, whereas Stoker intuited a Christian solution.

Monsters demonstrate. They come to life to teach us things about our world, and the dangerous spirits that we encounter in our lives.

Count Dracula gains great physical powers from his connection with the soil and precious metals, representing the use of currency inflation to suppress the lower classes, as described by Tim Price recently. He cannibalises and consumes the lifeblood of innocent people, after bewitching them with spells of magical words. He is served by gipsy serfs and can transport himself to multiple places, and move at will. He shapeshifts and is a master of beasts because he is animalistic and predatory himself. This represents the ethic of the ruling class that applies the law of the jungle, survival of the least compassionate and most ruthless, as it’s Malthusian, Nietzschean, Fabian, core value.

Note that at the time of writing, Stoker lived in a world where the memory of the liberation of the peasant’s revolt, Bannockburn and the reformation had banished serfdom and slavery in the homeland, for most people. But countries like Belgium were slaughtering and enslaving people en masse in the Congo, and growing wealthy. Scientific theories of racism were developed after the fact, as a justification for the great immorality of colonialism that had many of the former feudal lords of Europe so fabulously wealthy at the time. The industrialists were despised as ‘new money’, because their self-made free market wealth, created by providing goods and services, shone a judgemental light on families who’d gained their ‘old money’ by immoral means.

Vampires have no reflection because sociopaths, psychopaths and narcissists have no self-awareness or capacity to reflect empathetically. Their power increases in darkness and sunlight may burn and kill them, because the light of the world and the true law of nature reveals their wickedness for all to see, rendering them powerless.

Count Dracula feeds on women, seducing the upper-class newlywed who sought marriage to rank and status above love. He engages in sexual activity that is unproductive, before biting the intimately vulnerable part of the neck, symbolising the interruption between intellect and body, knowledge and life.

He never dies, and neither do his victims. Like the great corporation of state and feudal title itself, the power of reification and the gift of being eternally undead that is franchised out by the state to modern mega-corporations, make-work projects, and zombie banks.

Net Zero would be the perfect description of the Count as a consumer. He produces nothing.

There are ancient legends that you can trick a vampire by throwing a bag of rice on the floor. That will stall him because he will feel a compulsion to count every grain of rice, giving you time to flee. This represents the evil of the census, and the totalitarian urge to account for and control everything. Something we have to deal with on the ship, as the eco-warriors, clipboard cretins, nag-nazis, pronoun-police, true believers in the good-ideas club of Rome, that are the demonically possessed revenge mob of eco-femino-socialist bureaucratic desk drivers insist on lecturing us routinely about reporting any and every individual dead bird or fish spotted in the ocean. The kind of unproductive, parasitic people, who’ve crafted a religion where human existence is a sin, and rituals of recycling and veneration of David Attenborough the only means of atonement.

These people are the modern equivalents of Dracula’s familiars. The people who worship the state, whose religion is politics, and whose existence is funded by sharing in the deceit of our age – central banking.

(Can’t wait to see how they’re going to inflate their way out of this one guys, eh?)

How do we defeat this evil chimaera?

The cross, representing voluntary self-sacrifice, repels this parasitic predator. The modest middle-class bride, whom he covets, martyrs herself in order to set him free from eternal undead cannibalistic torment.

The feminine is the question in prayer and the mother of God. The teacher, and the leader, like Abbess Hild.

Women are suffering most in this world’s twisted version of state-sanctioned economic fascism. Told to worship the economy, and to become masculine, the transgender crisis is an unpredicted but possibly inevitable result of sixty years of self-sterilisation and politics as religion. The family has been reduced from clan, community and kin to nuclear family, atomised individual, and childless desolation. Inflation eats away at all of the leisure, beauty and joy that constitutes a proper life, and the story that all progress depends on the throwing off of all layers of oppression caused by hierarchy, rules or reality has brought us to a point of mental illness, bordering on civil war proportions.

My grandmother couldn’t understand why women wanted to become men. Luckily she never lived to see the ruin we are bringing to our young girls now, or to the demented support for the recent school shooter to be cast as the victim in last week’s killings.

The feminine needs to be brought back into our society, and not simply used to feed our vampiric overlords. The Devil is the accuser, but the feminine is the sacred questioner. The guide.

I see how my wife struggles to raise three children by herself, for most of the year when I’m away. And I look at the traditional little fishing community of Whitby and recognise that we are mourning the loss of something essential. Community.

I should have been a day fisherman, on a little potter. I should be home with my wife every night, and apprenticing my son by myself, in the ways of the sea. We should pay for our home in three years, not thirty. We should know everyone in our world by name, and live in a clan of shared values, kinship and trust. Nobody should come from the state and stand in the way of our God-given right to feed ourselves, warm our homes as we please, and live our lives without license. And at the very least, not use our own money against us, and coerce us to put untested dangerous compounds into our bloodstream. Something not even Vlad the Impaler or any tyrannical aristocrat ever had the power to do until now.

Bram Stoker died in 1912, two years before the Great War, when Whitby Abbey was bombarded by German Naval gunfire, bringing it to almost total destruction (what we see today was partly rebuilt in 1920). He did not see the ultimate effects of the evil spirit of his age, but he did manage to articulate it perfectly, in the creation of his Dracula character.

Nothing is resolved. We are still fighting world war one because the cultural seeds of its origins have never been addressed. The spirit that drove feudalism, the bad bits of colonialism, fascism, conscription, debt fraud, inflationary theft and deadly socialism is still alive and well, stalking us. Veiled in darkness but walking in plain sight.

Stoker understood the spirit of his age. Do we understand ours?

We still have vampires, feasting on us from above. But we have the supporting cast of zombies, clawing and attacking us from the side. The spirit of our age is not just the inversion from the book I Am Legend. It is the unholy alliance between the animated corpse of the aristocratic parasite and the animated corpses of the materialistic masses.

Their desire to consume the living shows us how the terrible forces of Jacobin resentment and fraudulent finance exploits our need for community, in order to sustain itself. Their nihilistic, spiritless hope for destruction shows the revolutionary instinct for what it is.

Unlike the vampire, who can be killed with truth and martyrdom, the zombie has no clear way to defeat. Zombie hoardes are to be survived. Some versions of this fiction are won by a variation on chairman Mao’s doctrine: ‘If we can’t change their minds, we’ll swap it for a bullet’.

Other versions like World War Z, involve partially infecting yourself with the zombie virus, and acting like a zombie, rendering you invisible enough to hide in plain sight. Walking against the direction of the mob is the only sign that you may not really be infected.

Covid snitches and SS informants proved that thesis incorrect.

The zombies accuse us of being ‘unsustainable’, ‘bigoted’, ‘intolerant’ and ‘consumerist’, because they have no self-reflection. Their accusations betray what they themselves are guilty of.

I became a Christian when I submitted to the realisation that we are religious creatures. We can only live in this world, inside a story. And did not like the return of idolatry and pagan sacrifice that I saw coming back to us, these last few years of lockdowns, masking, the deification of the state, race riots, transgenderism, Gaia worship, the outlawing of natural rights, farming and fishing, the nihilistic attacks on consent.

The ceremony of innocence is drowned, said Yeats. The widening gyre that brings mere anarchy, is resolved by finding a centre.

Discovering the keys to the kingdom of heaven, like King Oswiu, is now what I strive for. That involves paying attention to the greatest, eternal spirit, the love, truth and joy of creation. That involves standing in contrast, in opposition to the spirit of the age.

Even if it kills you.