Firstly, welcome to the recent wave of new recruits. I hope you have fun here. Please feel free to comment, question and correct me. I truly appreciate what I learn from all of my new Substack friends.

Start writing today. Use the button below to create your Substack and connect your publication with Captain Yankee Jock

Importantly, I must thank Steven, Chad, Alex, Christian, Daniel, Tanja, Andrew, Joe, Tim & Jody for their social & financial support. I did not expect to have so much interest in this blog so quickly, and I’m very grateful for your online friendship. I hope I can repay you all in kind and that we can all meet in person someday.

In response to these readers’ kindness, public support, and generous pledges, I am activating paid subscriptions this week.

This is purely to provide those who wish to be stakeholders in this particular voyage with a way to show their support and shamelessly influence my decision-making to their own benefit.

I will not be limiting any of the usual content. I simply want to speak to anyone, and everyone that I can, and continue to build this little fleet of dissidents to a more formidable number. ‘Loose Tweets, Sink Fleets’, may yet hold true, but hopefully, we’ll sink the enemy before we go down ourselves!

And if you have the patience to get through one of my epistles, then you’re my kind of person, and welcome aboard any time!

However, by way of a premium bonus, I was thinking of recording some no-holds-barred recordings of conversations between myself and some fellow seafarers, and possibly, eventually, some meetups, which I feel subscribers should have exclusive access to. Those who donate will be able to request what happens next, in the Yankee-Jocker community.

Watch this space.

____________________________________________________________________________

It is hard to describe how intense these last few weeks have been. Moving from ship to ship is challenging enough as a freelance Master Mariner, but changing sectors entirely has brought another level of complexity. It has taken every ounce of energy to get through each day because so much of what I’m doing now is completely new to me.

I’ve gone from moving passengers between various offshore platforms and ships to laying anchors, acting as a diving platform for air divers, and doing subsea construction. Learning anchor-handling as you go has turned out to be slightly less difficult than I perhaps once imagined. Just don’t touch any of the buttons if someone is standing in the way, or they’ll get maimed or die. It’s pretty much that simple. But the amount of regulatory compliance you have to deal with when it comes to divers is just next level.

However, this vessel is the total opposite of what I’ve become used to. She is a pug-nosed, ugly duckling, with a flat-faced bow, and a flat bottom. These design flaws were intentional so that her tonnage stays below the critical 500 Gross-Tons that would incur additional taxes, port fees and expensive regulatory compliance issues, as she enters the next category up. The upshot of which is, that she might be a powerful workhorse, but steering her in a straight line is like trying to do ‘no-handies’ on your bicycle, with a couple of pot-bellied pigs wriggling in your panniers and an excited black lab going through your tabasco-laced packed lunch on the handlebar-basket.

In short, quite difficult.

I recovered the mooring spread from the drilling site close inshore to the Morayshire coastline last week, manoeuvring with the computer-aided Dynamic Positioning (DP) system. Distances are difficult to judge at night, and the diving/energy company client reps wouldn’t keep quiet on our return back to port. I had to politely request their silence before my final approach. The sort of thing that a self-made company owner who wore his Omega Divemaster wristwatch and drove a smart sportscar down to our dirty little fishing port doesn’t usually like to hear.

With two metres of clearance either side of the fifteen-metre-wide ship, the harbour entrance at Buckie felt pretty tight. Particularly with a following swell. But after several runs in and out, I was starting to feel fairly confident with this vessel. At that port, my old mantra from the cruise liners seemed to work well: ‘Small Speed, Small Damage’ – something my wonderful Bulgarian training officer, Atanas, used to say.

After liberating all the books worth reading from the local charity shops, we were to depart Buckie for the next job in Whitby, North Yorkshire.

Whitby has turned out to be a different kettle of fish.

Poetically, we headed North to go South, stopping off at the coastline of the Cromarty Firth, by Invergordon. This great natural harbour, along with some other Scottish ports, has long been a haven for the Royal Navy in times of war, and long been neglected in times of peace. It is now where oil rigs go to die, and where wind turbines come to life. It was the setting for the Invergordon Mutiny in 1931, the last mutiny in the British fleet, and the historical incident that got Britain off the gold standard.

It is a harbour I know well from my days in geotechnical drilling and supply ships, and I love the haunting backdrop of the distant snow-capped highlands. But what I don’t love is taking a vessel with 4.5 metres draught up onto a beach, with a tidal window of a couple of hours to do cargo operations, with a 3-knot current on the beam.

That operation took me well outside of my comfort zone, and I did completely lose the heading a couple of times, but I got her back and did the job without serious incident. It was a stretch, but my confidence was building. I did a thing! (As the semi-cancelled Jeremy Clarkson used to say).

The next day and a half was a strange time. We steamed south at full speed, which on this vessel is an average of 7 knots. (Some people run faster, but in fairness, they don’t have a 350-ton deadweight). For two days we were rushing South but had no confirmation of our destination. Would it be the offshore job site, or would it be the harbour?

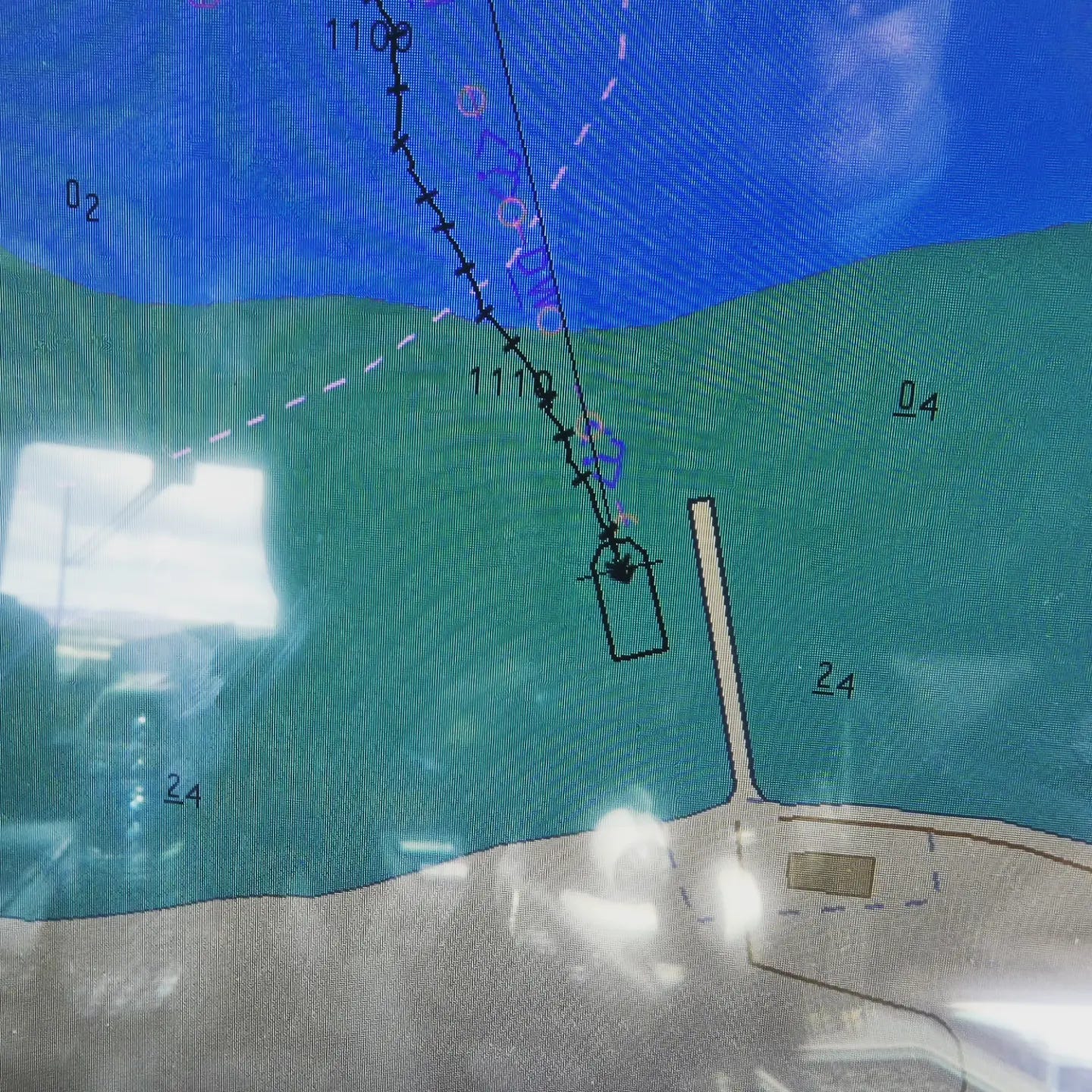

I had pleaded for the harbour. I convinced the owner that with the limited tidal window at Whitby harbour (it dries out in the river to only 30 cm charted depth), that it would be worth potentially delaying going to the site despite losing £15k per day because the North-Easterly weather closing in could be dangerous for us. And with a deck full of chain, we were loaded to our marks.

Setting off on Thursday lunchtime, it wasn’t until 7 pm on Friday that it was confirmed we should go directly to Whitby, instead of dropping the cargo of clump weights (Giant 20-ton anchor weights made of clumps of chain) at the site.

It’s hard to overstate how draining it is to wait for other people to make decisions when you are already underway to an unknown destination.

I had been so concerned with the operation plan for unloading the anchors and laying the ground chains per the survey plan, and trying to make sure I wasn’t overloaded or going to be unstable during lifting operations, that I hadn’t spent any time at all studying the sailing directions for Whitby.

I did read them, and studied the tides that evening, before turning in for the night. I confirmed the berth was clear, and sent my arrival documents to the harbour authority. I left night orders to set up on DP about 2 nautical miles from the entrance and wait for the high tide in the morning.

We are the widest vessel that can go into Whitby, but the narrowest point is at the bridge. That is the same width as the entrance to Buckie, just shy of 20 metres, but it was inside the harbour and sheltered. the actual entrance is wider than what I’ve already been doing with her. How hard could it be?

I slept well, confident enough in my plan for the morning.

I got up at 4 am, and contacted the harbour:

4 am – ‘Yes, no problem. We’re expecting you’.

5 am – ‘Yes, no problem. You’ll just need to wait on Fish Quay. There is another ship on your berth, but we’ll get them to move’.

5.15 am – ‘Um, there’s nobody on board this fishing vessel so we can’t move it. You may have to wait at Fish Quay until the next high tide’

Me – ‘Sorry, I can’t take the ground. I need to keep 1 metre of water below the keel’.

They phoned round.

Nothing.

Eventually, they figured out the boat was newly built, so it must have come from the only shipyard in town. You know, the one that builds fishing vessels. The kind that don’t get a crew until somebody buys them. But the yard didn’t open until 7 am, which was already High Water.

By 0800 they confirmed that there was no crew available until the afternoon, but that the berth would ‘definitely be available by the next high tide’.

Sitting in DP. Waiting, waiting, waiting. Sending the profit margin up the funnel for no discernible reason. All the while, the horrible stormy weather from the North-East that we’d been so careful to get ahead of, was building.

The tide went out. The tide came back in. The lungs of the earth inflate and deflate with benevolent, yet indifferent, regularity.

Twelve hours in limbo, after a day and a half of not knowing.

The threshold of uncertainty is a deep and wide obstacle, overcome only by patience.

I caught up on paperwork and tried to nap. When that didn’t work, I read half of Clive Lewis’s Mere Christianity, which I bought for 50p in Buckie. (I really need to translate some of these older books I read into more modern terms).

Waiting, waiting, waiting, waiting.

As the waves build, the swell worsens, the wind gusts and the skies become lead-grey. The mist closes in, gale warnings come on the radio and the light dims, and everybody sensible gets tucked up in port before you and heads home.

Waiting.

When we have 3 metres under the hull, I retract the ‘drop-down’ thrusters and reduce our draught from 4.5 to 2.8 metres.

Me: ‘I’m going in before it gets worse’.

Whitby Harbour: ‘Erm, OK. You’ll have to wait until 7 pm when the boat crew comes down to clear your berth for you’.

Me: ‘OK, I’ll wait at Fish Quay’.

I started for the breakwaters.

I did all the things you should do. Tested my steering. Lined up on my marks a long way off. Got my radar, PIs, and ECDIS working for me. Cleared every distraction. Posted crew on either side of the vessel to report clearance distances. Kept a nice slow speed of 4.5 knots, and made a steady approach.

Whitby harbour has the only North/South aligned harbour entrance on the entire East Coast of the British Isles. This meant that the swell that had been building all day was now up my arse, about 30° (degrees) off my starboard quarter. (I say starboard quarter, but this ship is bi. When manoeuvring in close quarters we flip all the controls to the aft station and drive in backwards, so the bow becomes the stern and vice versa, and everything is very confusing).

My line was good. The piers were opening and staying open.

OK, I was drifting a little to the east (my left-hand side looking in the direction of travel, but weirdly, the starboard side, but kind of the port side coz we’re going backwards now). Within acceptable parameters, so I was just steering a little high to compensate.

Until the entrance.

Boom!

A big roller hit my backside and lifted the entire ship and plopped us down in a different spot.

Boom!

Again.

Now we were closing fast on the pier, and my heading was all wrong. I was adrift, set down way to the East (weirdly to port/starboard).

The radio transcript from the deck was something like this:

‘Looking good, passing clear’.

‘Side distance 4 metres clear. Line is good’.

‘F*ck! F*ck! Astern! Abort! Abort!’

[Note: Curse words are activated by the part of your brain that detects obstacles.]

‘Closing! Closing fast! 1 metre to the pier!’

The frequency, malodourous tone and pitch of the comments from the deck acted like the increasing beep of a parking sensor when your car is reverse parking too close to an immovable object.

Thank God (and Rolls Royce) for 360° rotating azimuth thrusters, is all I can say.

In a matter of seconds, I’d gone from a reasonably peaceful but focused approach to an alarming possible emergency and imminent allision with the pierhead, which was now dead ahead of me.

I put my left-hand (Port side in my mind, but actually starboard) Azipod facing astern (actually forward) and set it to 100% thrust. My right hand (Starboard to me, port in reality) Azi facing due West (Starboard. No. Port. Um. Whatever. Away from the big concrete f*cking pier that I was about to crash into). Bow (actually stern) tunnel thruster 100% hard to starboard (port).

SCREAMING ENGINES!!! The steelwork rattled and groaned. The only thing I could see was the gap between the concrete and my boat.

The swell was so severe that the thrusters were out of the water and in mid-air, as often as they were submerged. The guys on deck told me that when the ship was rolling and only one side was in the water, the other side was shooting jets of seawater up into the air like a fountain. Other times she was just gasping and cavitating, with no water at all. That’s why my engine movements were having a lesser effect than I would normally expect.

My hands gripped those pods and thruster controls like a mountaineer clings to his lifeline after a fall.

We got so close to the pier, which was lined with tourists standing stupidly close to a ship that was capable of taking them out, that one chap on the shore was able to offer some helpful advice.

Randomly helpful Yorkshireman: ‘Oh mate. You don’t want to come in just now. You wanna wait until 1.5 hours after High Water for when the rip tide stops. Everyone knows that’.

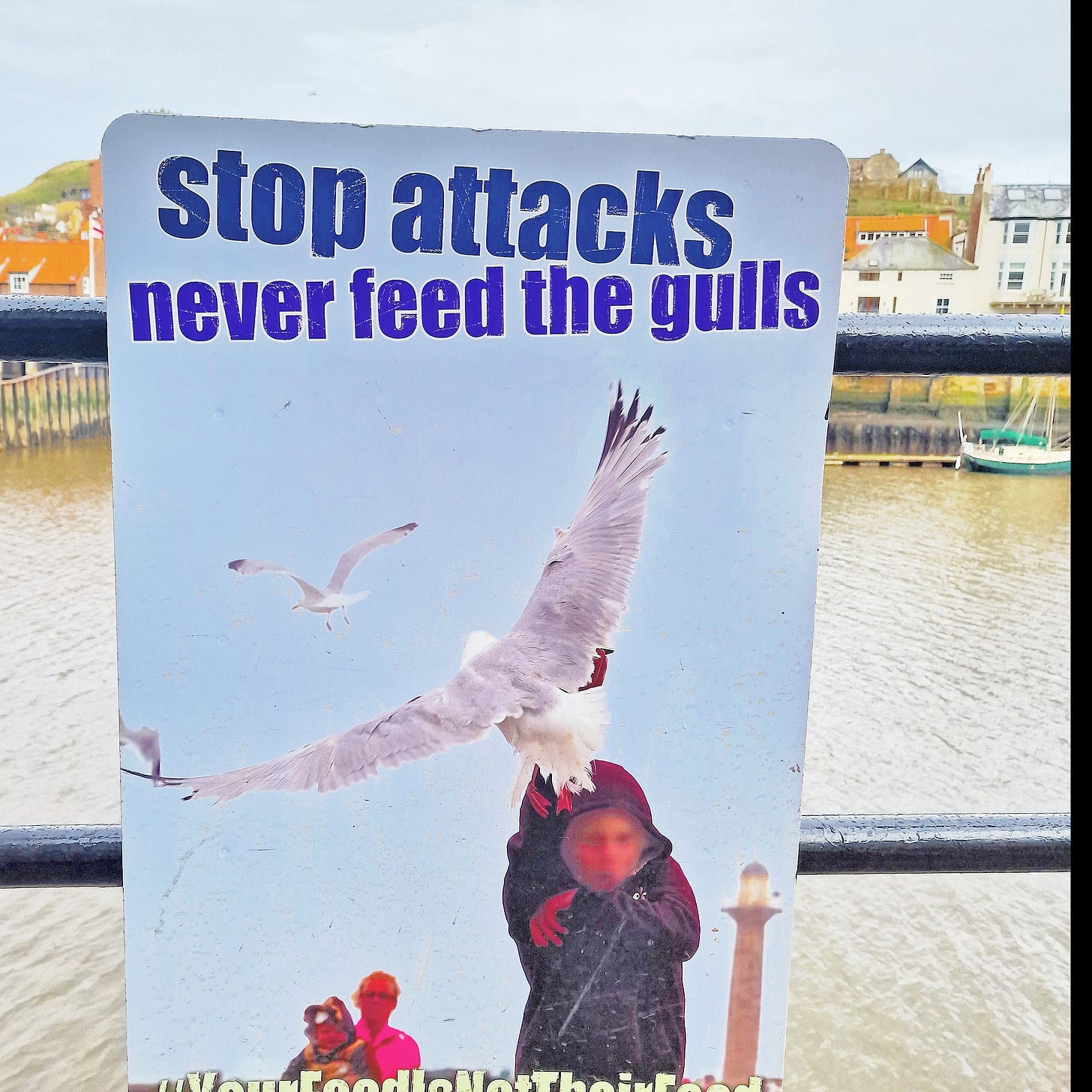

(He actually said that, but I didn’t find out until several hours later. I later confirmed his statement with the harbour authority and a couple of old boys at the local fisherman’s club. There is indeed a permanent cross-current at the entrance to the pier extensions at Whitby, which partly slackens for a few minutes, about 1.5 hours after the flood completes at HW. That old fishy b*stard. He needs my old job writing the sailing directions for the Admiralty).

Anyway. I saved it.

Luckily, I had enough power and experience to get out of that at the last minute. I thanked God I’d spent all of last year on the Vomit Comet, manoeuvring close to danger in strong tides. I have become accustomed to ship handling in that kind of proximity to danger and knew how to deal with it without panicking.

The jelly legs don’t come in the moment. They come after.

Safely tucked inside the breakwaters, after three minutes of wrestling sideways against the cross-current at the entrance, when we were safe – that’s when my hands started shaking and my heart rate got away from me.

Effing and jeffing did occur, as the wave of stress and adrenaline passed through me in a surge of relief.

The chief mate and the crew applauded me for doing well and recovering the situation. However, my pride and confidence were seriously knocked for having gotten into it.

And then we still had to wait another flipping hour and a half at Fish Quay before going through the bridge with two-metre clearance on either side, because the fishing boat owner had still not arrived from Timbuktu or wherever!

As I eased her through the swing bridge it was after dinner time on Saturday night, and there were crowds of drunken Yorkshire folk on Stag-do’s and Hennies shouting abuse at me for blocking the main road through town and interrupting their drinking for ten minutes.

I blocked it all out from my mind, and they were but a blur, like the potential casualties standing on the pier I had just narrowly avoided destroying. Although, I’m fairly certain I heard the phrase ‘Boat W*nker’! a couple of times.

It’s the glamour and sophistication that keep me in this game.

We made fast at Endeavour Wharf, close to the replica of Captain Cook’s famous Whitby-built ship, the Endeavour, and I promptly went ashore and violated the company’s ‘zero-tolerance’ alcohol policy, not caring in the least if I never saw this boat again.

Times like that, you really do ask yourself ‘what am I doing with my life? Why can’t I just work in Asda, or something normal’?

But then, we had five days in port to recover, and I went back out. I absolutely nailed it the next time. Got out no problem, moved a special marker buoy, laid a five-point anchor spread at the offshore job site, and got back in the next morning with a strong cross current, and 25 knots of wind on the beam. And I was doubly glad I nailed the arrival on the second occasion because I was told beforehand that the company owner was watching on Whitby Harbour’s webcam that time.

The trick was not to approach in a straight line, but to aim directly for the West pier, as if you’re going to crash, and just have enough faith and alertness to know and trust, that at the last moment, that cross-current will set you bodily to the East, wher you need to be.

Interesting that the root word for Cardinal comes from ‘hinge’.

I even laid a 20T clump within a few metres of some UXO – Unexploded Ordinance, that sat menacingly close on our seabed survey sheet. Most likely some bombs dropped by WW2 bombers who needed to lighten their load, in order to conserve fuel on their homeward bound run. It is estimated that there are 500,000 unexploded munitions on the seabed, within the boundaries of offshore renewable energy sites in the UK. 10% of all bombs and 30% of all sea mines from WW2 remain in situ, and in varying states of decay, so I was quite relieved that I didn’t set one off.

Overcoming obstacles is the real thrill of this job.

The seamanship here is real boy-scout problem-solving at every turn. Dealing with multiple clients, marine warranty surveyors, mooring analysts, divers and the HSE requires a reasonable understanding of the various business models, incentives and financial arrangements at play. Knowing all of the technical skills, and putting them together is one part, and being able to articulate and persuade external people is the other. And when you stretch yourself, and get it right, and you’re in the zone and you pull it off perfectly, it is some feeling.

When I’m ship-handling, and I pull off something difficult, nothing else exists.

You get to feel something amazing. Like temporary purity. A moment of strength, that comes through cooperation with all of the external forces acting on your vessel, and from a perfect command of the systems inside it.

That’s the buzz you do it for.

Knowing that if you can align yourself completely with reality, there is no limit to your potential.

And the travel isn’t so bad either. Whitby is an absolutely amazing place.

It’s a part of England that is still proper England. It’s actually much more than that. It is a place with its own spirit, and its own people, who are still a people who are entirely ‘of’ this place.

But more on that in part 2…